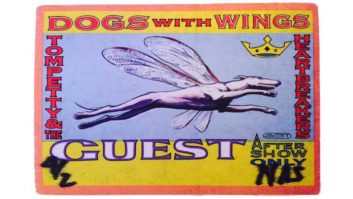

Audio luminary Robert Scovill delivered the keynote address at the Webster University AES Student Section’s 5th annual Central Region Student Summit. A six-time TEC Award winner with more than 3,000 live event mixing credits under his belt, Scovill has tackled FOH for Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Matchbox Twenty, Prince, Rush, Def Leppard and Alice Cooper, among many others. When not behind the mixing desk, he serves as Senior Market Specialist for live sound for Avid. For the keynote speech, Scovill spoke to an audience gathered in the Loretto-Hilton Center, on a stage set for a production the 1960’s musical Beehive. The following is a transcript of his message:

By Robert Scovill.

I’m surprised by the set here. I feel like I’m on the stage of a Nickelodeon TV show or something. I took note of the beehive thing [gestures towards set]. I don’t know if you know it, but in the concert community, we have a term that’s called “whacking the hive,” like if you’re going to wind somebody up or you’re going to complain to upper management about anything, it’s called whacking the hive. “Hey, I’m going to go back in the office and whack the hive for a few minutes.” So this, [as the stage for] my speech today, may be perfectly appropriate.

Thank you for inviting me here. It really is an honor to be here at AES in St. Louis. I don’t know if many of you are aware of it, but I actually grew up very close to here; I grew up in Valley Park and spent all my formative years there. I actually got my first exposure to concerts there at a really young age, at places like Kiel Opera House, Kiel Auditorium, certainly the Checker Dome, Mississippi Nights–and they left a big imprint on me growing up. I grew up listening to KSHE here in town at the time when it was totally a progressive rock station. That’s where I got my music education, I assure you. At that point in history, KSHE was a pretty cool thing. They had a lot of interviews with producers and famous engineers and it really stoked the fire of interest for me to get into this business.

So, I hope you appreciate today that this is kind of surreal for me, to be able to come back; for the kid from Valley Park to come in here and speak on the professional audio industry. It’s a neat thing for me.

Over my career, I’ve given a number of speeches; I’ve done this numerous times. And today I just want to take the opportunity to get on the record about a few things. Certainly regarding some topics in our industry and by industry I don’t just necessarily mean the live sound industry. I guess we could call this, this is going to be, an in-person blog, because I’m sure one of you is recording this–it’s going to end up on YouTube, it’s going to end up on the internet somewhere, so I’ll get to go on the record here a little bit.

For those of you that have tracked my career (I know you’re out there), my first thing to say to you is, “What are you doing with your free time?” There’s other things to be doing besides tracking my career, I assure you. But that said, if you’ve been following me, then you know that live sound, and certainly the recording of music, has been a passion of mine since very early in my life. And there’s really a little bit of a distinction in that statement because, believe it or not, while we get lumped in–being audio guys–as techno geeks. We get caught up in the minutia of the technology. For me, it really had nothing to do with that. It was all about music for me. If that piece of technology didn’t have a way to make music or have music coming out of it, I just was not interested in it.

So while technology fascinates me, its ability to make and contribute to the music process is what really trips my trigger. And you know, certainly live sound ended up becoming a big passion of mine. The majority of my career has been spent in the live sound community, and reflecting on my first 30 years as a professional in live sound, I’ve always felt like live sound was just on the cusp, just to the breaking point or the tipping point of getting taken seriously; to the point of maturing and getting taken seriously, certainly by the golden ears of the audio community.

There’s countless analogies or metaphors for this. Sometimes you could think, well, live sound guys are like M*A*S*H surgeons, compared with recording engineers who fancy themselves as Harvard neurosurgeons. Or you could say, maybe live sound guys are the gritty and grimy drag racers compared to the glamour and the glitz of the recording engineer and producer as an F-1 or an ME racing car, right? It has that tone to it. And it’s always implied, “second class citizen,” and I think that’s true until you really dig down a bit and start to realize hey, the M*A*S*H doctor actually has a great deal to offer in terms of saving the patient. Which I think is really fitting for how it works in our industry today, in live sound today.

For my money, the live sound discipline is really professional audio at its purest. It really is. It is an extremely complex combination of science and art that demands, absolutely demands, respect and competency–and any lack thereof, it will display with brutal honesty. In many ways, it can be a means to show what pro audio can really, really do. And what it can contribute to the musical experience for the most important person in the house. I’m not talking about the lead singer’s wife. I’m talking about the fan, right? That’s who we are working for. That’s who we’re doing this all for. This is where I want to dig in and speak to you today.

First, about an industry in which the live sound community is an integral part of the over-arching business. Live sound currently is part of an industry that feels really disjointed and out of synch. That’s my take on it, and I’m not going to be all doom and gloom here today, but I think it requires some looking inward and some examination of exactly what we’re doing.

There was a time not all that long ago when the high-quality listening experience, be it recorded or live was the implied, or even the stated, goal of the recording community. It was there. It was palpable. You could touch it. Music was really the vehicle, and professional audio, be it recorded or a live sound, was the gas that made it all go. We wanted music to have a sound that led the fan to a listening experience that he or she did not even know existed, didn’t even know it was possible. And make no doubt about it here, we were all in it—producers, engineers, promoters, fans; we were all looking for that really magical combination of performance and high-end, quality audio. That was our thing. That’s what we wanted. That’s what made us all tick.

The Golden Era for this, in my opinion, was the 1970’s and 80’s. Unless you experienced that era, the 70’s and the 80’s, you can’t really process how out of synch today’s music industry machine is. By that machine, I mean the musicians, the recording community, the live sound community, the record and concert promotion industry. They’re just very out of synch in terms of their identity.

There was a time when these segments of the music industry seemed to be firing on all cylinders in regard to what the end play was, and they all used similar metrics to do it. The artist had to have talent and they had to have something to say either musically or lyrically. They had to then create a product that was well engineered and recorded, and after release, the radio machine or [other media] would promote the album. Then you needed a record company on top of it with the mechanism to tap into your fan base and energize them with product through really meaningful distribution. And this was likely followed by a concert tour that served to promote not only the music but the artist.

When this worked really, really well together, you ended up with artists, as well as the people that produced and promoted this music, that became icons, and subsequently legends, of our industry. I totally revered this process and I can remember many, many times discovering new music and my initial thought would be, “Man, I cannot wait to see this live. I cannot wait to see this in concert; it’s just going to be stunning.” And the times that I now discover music, and have that visceral response to it, is fleeting. I’m not sure why that is. I think because, on a whole, the recorded artist today is not really developed and promoted as a great act or performer and it lends itself to the audio production in turn ending up being uninteresting to some degree. It’s like it has lost a piece of its interest and its drive.

There are obviously numerous contributing factors to this over the past 20 plus years. We could go on for hours about it. But for my money, at least from my perspective, I think this [situation exists] primarily because the agenda for making music has slowly just completely flipped upside down.

Believe it or not, there was a time–I want you to think about this–there was a time when the live performance existed before the recording. Just digest that and think about that for a minute. Today, very few artists spend any meaningful time honing their craft in front of an audience. In today’s music scene, I’ve actually worked with artists that go into pre-tour rehearsals with the express goal of learning how to play their own record. Think about that for a minute. It’s essentially the same mindset as a cover band. I’ve heard artists actually say, “I can’t sing it in that key.” “Well, you recorded it, didn’t you?” There’s a disconnect that is happening there. It’s like you’re covering your own songs or you’re learning how to cover your own songs, and to me, that feels very, very backwards.

Now I don’t want to stand here today and sound like some old curmudgeon who’s stuck in the romance of the past. That’s not my goal here today at all, and I’m certainly not here to imply that the old way was the end-all, the well-oiled machine with no challenges to be addressed or solved. Believe me, it was rife with challenges in terms of making the recording process economically viable for the artist, making the distribution process nimble and able to respond quickly to demand. It was very difficult, aligning all the promotion processes in order to create the perfect storm of distribution and marketing, and on and on. It was tough.

The analog model of recording and marketing and distribution and live performance was a formidable mechanism to manage and it was not for the meek, I assure you.

But what I have witnessed in my time: In an effort to streamline all those processes in terms of efficiency and finance and work flow, we’ve also stripped away the artist’s development as a performer and their ability to in turn grow as musicians and artists and entertainers. It essentially made them disposable by many counts, with their cultural legacy–their musical legacy–just measured purely in revenue numbers. You know, Pollstar, Billboard—that’s the lasting legacy; it certainly doesn’t seem to be the music and their contribution to the art. And if that is the case, I really fear that we’ve eviscerated the music business of its soul. That really is where it lies.

At this point you’re probably saying to yourself, “Okay, Scovill, where are you going with all this?” So I’ll ask you to ponder this; this is the tipping point: Before the realization and the execution of digital audio, there was the promise that digital audio held for capturing and preserving the great performances of our industry, coupled with the distribution and portability potential that existed for digital music, followed by what was billed as the ultimate listening experience for the fan. This was all a really romantic and really enticing possibility. Who would not have wanted these things to happen? They were all really admirable goals and it completely energized this business, this industry. It filled it with some excitement that I’ve never seen since in my lifetime. It was really, really something. “When we were on the other side of digital,” believe me, everybody was like, “that is the answer, man; that is where we’re going. It is going to solve our challenges and our problems. It’s going to solve it, not just Band-Aid it. Solve it.”

So what happened? What happened? You could find countless pundits, pointing their finger at digital technology as the direct–not indirect, the direct–reason for everything from the decline in musical talent and creativity, to the death of the music industry as we know it or knew it. Let’s face it; you could find folks that would blame digital technology for everything from the housing crisis to teen pregnancy. I’m sure it’s out there somewhere—Digital Audio: The Devil Incarnate, right?

But I submit to you this question today. Is it really the technology’s fault? Is it the designers of the technology that are to blame here? In my own experience, I’ve never experienced a technology that has made any final decision—ever—on how it should be used. It’s always, 100% of the time, a choice that is conceived and made by the human as whether or not to, say, Autotune a vocal in lieu of another take; sample someone else’s music and include it in their composition and claim it as their own; master a recording using compression techniques that only digital technology could afford you, with no other stated goal than to just be louder than everyone else with your recording with no regard to the negative consequences of sonic quality on the end product; post a WAV or an MP3 file onto a server that exposes every listener on the internet to that master quality work without any intent at rewarding the artist financially for his work. Those kinds of decisions are not made by the technology. They are made by the human.

The last time I checked, inanimate objects such as compressors, the gun, the software, the knife—the bottle of tequila for that matter—have not and should not be held accountable. I think if you check the historical record since the beginning of time, [you ’ll find] when vanity and greed sit at the head of the table, some questionable decisions are going to be made. They’re sure to follow. Last time I checked, vanity and greed are hard-coded human features—not features that are even part of a code base in digital technology.

Now, while there is certainly a lot of noise about digital technology being held accountable for the decline of musicianship and the musician’s ability to perform music live, and the death of the music industry, strangely on average, we don’t really hear that kind of negative rhetoric about concert sound technology or live sound in terms of digital technology being the path to the demise of quality concert sound or the death of the concert sound industry. We don’t really hear that. It’s not really the undercurrent that’s happening right now. And in fact, I would say to you that it’s quite the contrary.

My gut tells me this is primarily because the positive aspects of digital technology on everything in live sound from work flows to sound system design and operation to sound quality—even the greening of the concert industry—are so positive in historical context, the adoption of digital for live sound is going to be seen to happen very, very rapidly. I think it’s going to happen very, very quickly. It is happening quickly.

Now certainly, digital technology in live sound is not with its detractors. They’re certainly going to be out there, but overall, I think you have to view it as being strongly embraced by the industry as a whole. It’s happening very rapidly in an industry that typically moved very, very slow.

But for certain, there’ll be diehard analog guys in concert sound and they’ll hold onto it very tightly, much like guys hold tightly onto vinyl and analog in the recording industry. But the genie’s out of the bottle. They’ll certainly not be representative of the industry as a whole moving forward. Nor will they be indicative of trends in the future; it’s just not going to happen.

My prayer, though, is that we as the live sound community really adopt and deploy digital technology and stay focused on that core agenda: excellent audio for live performances. That has to be the agenda. If we serve that master, we will do the industry, and more importantly the music, a lot of justice. I think we stand [poised] to be like that M*A*S*H surgeon and revive the patient.

As 2011 comes steaming into focus here, where do we stand in live sound in regards to that transition to digital technologies and work flow? Let’s discuss here for a second, “What are the ‘gotchas?’” What are the things we need to keep tabs on?

We’re currently, I mentioned this on a couple of panels over the last couple of days, we’re currently in an age where, technically speaking, the speaker systems that we have provide a level of resolution and performance and coverage for the audience area unlike anything we’ve ever had. It would have been a mere dream even just a couple of decades ago. The mixing and processing technology are affording us ever expanding level of feature sets, flexibility, repeatability, that again was not even conceived of or thought feasible not all that long ago for live sound applications. Consider this: the choice of instruments and sound that the musicians have at their disposal has certainly never been greater. Yet, if today, if you were to ask folks what they think of concert sound quality, you would probably feel lucky to get a lukewarm response from anybody other than a really rabid fan.

Why is that? We got all the great stuff. Why is that? Given what I’ve presented to you early in this little speech here, it would certainly be easy to blame the declining quality of the music or the musicianship or the artists’ abilities to perform in front of an audience or even the sound of the buildings, any of that stuff. And some of these points are certainly going to have merit, but as I stand here in front of you today, what I’m going to present to you is that what is overtly apparent to me is that the cornerstone–the cornerstone of successful live sound is now and will be for the foreseeable future, the human being in charge of the console.

You. You are the thing that makes the difference here. You can provide today’s live sound mixer with the most scientifically accurate sound system, perfectly integrated into the most beautifully tuned space with the most prolific ensemble plugged into the most techno advanced console available to us and guess what? If the person mixing the event is lacking in even the most basic mixing skill, the ability to interpret that music and connect it to an audience using a speaker system and a mixing console, those shortcomings are now prominently on display in high definition for everybody to hear.

The technology is bringing us back to focus on the lack of what I’ve termed ‘mixing skills’ that exist for the live sound professional. I see it and hear it all the time. It’s even bringing into play their lack of knowledge of really basic audio principles. I see it happening continually.

In regard to pure mixing skills, the vast majority of the people that are out mixing live shows do not come from a studio background, where creating music and mixing music is a daily focus. So I constantly come back to, “Well, where do they get their skills?” Many who inherit the chair are really not even sound-related people. Sometimes they’re just road crew members for the band. Maybe it’s a tour manager who’s also mixing live sound or a guitar guy who they fall with and say, “Hey, why don’t you go mix sound for us?” etc. Some of them come up through the ranks of sound companies, but there the focus is on systems integration not mixing skills, not music creation or recreation. And some, like very many of you today here, come from educational institutions where you get to spend a lot of time focusing and honing your skills, even your mixing skills, It’s exciting to hear that we have mixing competitions, etc., but [there], you don’t get a chance to test them under fire. It’s harder, believe me, when somebody’s listening: somebody’s listening to you build [a mix], somebody’s listening to you or watching you make the sausage—it’s a little harder when somebody’s watching.

Consider the irony of that. We’re now in a time when relatively high-end mixing and monitor technology is available to nearly everyone. Everyone. The amount of technology and the resolution that you could listen in and work in and the amount of processing blah-blah-blah-blah—it’s just mind blowing what’s at your disposal. And when I say everyone, that includes the live sound mixer. The ability to record and mix countless tracks can now be done in the convenience of our homes or the convenience of our front of house position or our monitor position and this provides the means for the possibility of experimenting and refining your approach when nothing is at stake—especially for the live sound mixer in that he can now employ concepts such as virtual soundchecks to be able to work in absence of the band and to be able to really develop and refine not his system integration possibilities, but his mixing techniques.

These are all things that are sure to improve the skill set over time, but yet the key component is still missing. It’s something that existed in the old studio paradigm before we got to home recording, before we moved to that. And it exists only in a few of the bigger sound companies. That concept is mentorship. Mentorship. Someone to set the bar for you. Someone to show you the way around and most importantly, question what you’re doing, and then more importantly, lead by example. That is the piece of it that is missing.

Now don’t confuse it. We have plenty of willing manufacturers that are eager to provide you with operational training, but once done, you’re left to your own devices to establish a valid approach to mixing. And again, by mixing, I don’t mean operating the technology. I mean listening, anticipating, evaluating, reacting. To me, personally, mixing has very little to do with the actual console. It has everything to do with your ability to listen and then build an audio tapestry, first in your mind and then with the chosen tools. For the artist, the art exists here [pointing to head]. The canvas is just a place to display it. That’s the way mixing has to be for us.

What we need in respect to live sound is–I’m not quite really sure how to put it–but we have to avoid the fear of settling into a culture of operators, making live sound very utilitarian: turn it on, turn it up. It’s got to be more than that. The technology is giving us some stumbling blocks for that because it is so complex now and believe me, I’ve seen the future 10 years out and it’s going to get increasingly complex with increasingly more features and possibilities. We can’t lose sight of the idea that we need to use that technology to create a musical experience. We can’t get handcuffed by the technology operationally. And for me, personally, I would never want my legacy to be associated with a piece of gear. I don’t want to be known as the guy who, “Well he was great, but he could only do it on that console.” I don’t want to be that guy. I would much rather my legacy be the quality of work that I put out or even the quality of people that I built and sent out into the world. That’s a fantastic legacy to have. It’s probably what fuels my fire to teach and do workshops, etc. I love that concept.

I’ve used this example in a few different places, but I think Johnny Rotten of the Sex Pistols really summed it up pretty well when he was commenting on why he had destroyed so much of the Sex Pistols’ clothing and instruments and all the stuff that was fashion-related and technology-related to the Sex Pistols when it was being coveted by the Hard Rock Café. And his quote was, “Hey, it’s not about the stuff; it’s about what we did with the stuff.” And he just destroyed it all. He didn’t want people focusing on that piece of the legacy. That’s the way we have to be in the music business, I believe. It just has to be a musical ends.

Again, I’ve often credited Bruce Swedien with probably the most insightful quote in this regard, and I’ve paraphrased it many, many times: “No one ever went home humming the console.” Right? They just don’t care—what they care about is the music. It has to have a musical ends. And if not, question your agenda at every turn and always work under the premise that technology will never, ever be a substitute for talent and skill. Never. Not going to happen.

We as a culture of audio engineers need to begin to think–and more importantly hear–bigger and better than we currently do, and until we do, as live sound engineers, I assure you we’ll never move out of second-class citizen status. Certainly in the eyes of the engineering or the musical community. We’re always going to be seen as audio janitors.

In closing here, I feel compelled to share with you some thoughts regarding the recent loss of one of the true live sound icons in our business. In my career certainly I’ve been really, really fortunate up to this point to meet and spend a good deal of time with a lot of recording pioneers and certainly some of the true pioneers of sound reinforcement. You know: Bob Heil, Bill Hanley, John and Helen Meyer, Don and Carolyn Davis, the late Don Pearson, the late Bruce Jackson and on and on.

But recently I was really struck by the loss of one of these pioneers whom I had never met. I had never met him personally, but he clearly, clearly influenced my thinking and my direction and where I landed in pro audio: Owsley ‘Bear’ Stanley. Owsley passed away this week in his homeland of Australia, and for those of you who may not really understand Owsley’s legacy in regard to live sound–and I don’t mean his other extracurricular activities–he was really the driving force behind the Grateful Dead’s “Wall of Sound.” If you don’t know about this, I encourage you to look it up and study it. It’s a great case study, that along with many other live sound innovations during the 60’s and 70’s. He and the Grateful Dead and all that surrounded them were really true concert experience visionaries. They had bigger ideas. They challenged the existing machine to not only be bigger, but importantly, be better. Always better.

And they, along with promoters like Bill Graham, essentially conceived and built the large-scale live touring mechanism. They put it on the map. The motivation behind that challenge was simply to make the concert experience of the day the ultimate listening and cultural experience for the artist, and again–most importantly–the fan. And my hope is that we as an industry never lose sight of those kind of values. I hope we just never lose sight of it. If the recording and music industry have taught us anything, it should be that we do that at our own peril, right?

So, that’s all for me today. Thank you very much for listening. I appreciate you giving me the opportunity to say this and voice it. I’ve really enjoyed hanging out with a lot of you yesterday for sure and presenting on some of the panels. It was a great honor to do that. Thank you very much.