NEW YORK, NY—A client who insists on using just four microphones on a seven-piece band, including drums, might give the average engineer pause. But bandleader Glenn Crytzer, who has been immersed in the music of the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s for many years, is a stickler for authenticity.

“If you listen to anything from the 1920s, guys had to alter the way that they were playing when they were doing mechanical recording,” says Crytzer. “Playing the bass drum would make the equipment skip— but the function of the mic wasn’t to make the drums louder; it was to make the horns or the soloists louder.”

Crytzer is regularly found on bandstands throughout the New York area, where fans can listen to vintage jazz at 10 or more venues on any given night, he says, such as the Lincoln Center, the Rainbow Room and the Glen Echo Ballroom. His own bands—he also plays as a sideman—range from the Pegu Club All Stars quartet to the Glenn Crytzer Orchestra big band, and also include various small ensembles that perform vintage songs of the era as well as swing and New Orleans jazz.

Crytzer got his Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in classical composition and cello, but his interest in swing dancing, shared by an avid community worldwide, led him in another direction. “One of the things that I found really frustrating was that most of the dancing in the early 2000s was to DJ’d music. There were jazz bands out there, but there just weren’t bands that were playing the music that we really wanted to dance to,” he says.

So Crytzer picked up the banjo and the guitar and began transcribing and arranging some of the standards while also writing new tunes, some of which have been placed in TV shows such as Pretty Little Liars, Bomb Girls and Grace and Frankie. But while he imbued his music with authenticity, he found it a challenge at first to deliver a truly vintage jazz experience to his listeners.

The first step was determining the correct microphone placement, which Crytzer has refined through trial and error. “There was a lot of talking with different people, a lot of reading about what older musicians used and what equipment was available. I also got some great advice from [master sound technician/designer] Jack Burke at the Seattle Opera,” says Crytzer, who relocated to Seattle in 2006, after he graduated, then moved to New York in 2014.

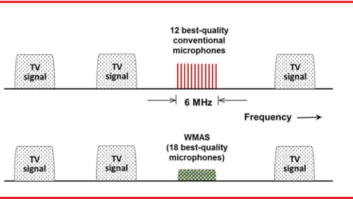

As noted in the technical rider for Glenn Crytzer’s Savoy Seven, a 1930s and ’40s combo that, like many of his bands, frequently performs at swing dances and competitions, “To get the sound we’re after, we mix the band acoustically using mic placement and by playing with dynamic contrast. It’s not okay to add more mics to this. We’ve tested this in many large venues and, just like the bands in the ’40s, haven’t had any issue filling any space we’ve played in.” The Glenn Crytzer Orchestra—five brass players, four woodwinds and a four-piece rhythm section—requires just three supercardioid dynamic mics and three wide pattern condensers to capture its big band sound.

Crytzer has released seven records to-date, the most recent being 2015’s Uptown Jump by the Savoy Seven, which was recorded at Peter Karl Studios in Brooklyn. All of his releases have been mono—a stylistic and a functional choice, says Crytzer, that ensures that his records can be enjoyed anywhere on the dance floor while also sounding authentic played alongside old records.

The recording process has also been a continuous learning experience, he says. “The best way to do this sort of stuff is with two or three area mics, placed carefully,” based on repositioning the band members until everything sounds right.

Other than editing together the best sections from several takes, “The only thing you can do in post is really mixing by EQ,” he adds. “What we’re doing isn’t intended to sound like a live performance. But we’re playing live and trying to capture that interplay of the musicians. The way that things are balanced on a record is going to be different than the way that it’s balanced in a live performance.”

Larger performance venues that regularly stage acoustic music are more likely to understand Crytzer’s desired mic layout. But, he says, “If I can do my own sound, I bring my own equipment. If the venue is too large for that, I send my sound rider, and it has to be signed-off before we sign the contract. Despite that, I’ve walked into a place, holding the contract in my hand that says it has to be this way, and people have tried to sneak microphones onto the stage.”

The biggest issue with less experienced engineers or at smaller locations, he says, is the lack of microphones on the drums. “I’ll walk into a place and they’ll say, ‘We have to put a mic on the drums because they won’t be present.’ They’re not supposed to be present [but] that’s foreign to a lot of people’s understanding of how to do sound,” he says.

Perhaps the biggest step toward an authentic live sound was dispensing with stage monitors, he reveals. Once, at a big band competition, Crytzer recalls, the sound guys later asked him why his band, with so few mics, sounded louder than the other band. “I said, it’s because they’re playing with monitors. They have all the sound blowing back at them, so they don’t play as strongly.

“It’s really the first music that developed alongside technology. Prior to that, everything was acoustic, and after that, everything was electric. So this era of music is really fascinating because it affected the way that people played as new developments in technology, both electric and acoustic, came about.

“Part of my goal is to share some of that history. The other goal is to give people some idea of our aesthetics and what techniques help us to achieve those aesthetics.”

Glenn Crytzer

glenncrytzer.com