In 2006, Casey Crescenzo set out on an ambitious project, especially for a 23-year-old: to create a multiple-act concept album in six parts that would take well over decade to complete. The epic journey, which at first glance is something one might expect from Anton Checkov rather than a rock band, is set at the beginning of the 20th century and tells the fictitious story of “The Dear Hunter.” This month sees the release of Act IV: Rebirth in Reprise, a complex and delicately produced 15-song collection that sees Crescenzo at the pinnacle of his writing, arranging and producing capacities. Pro Sound News spoke with Crescenzo about how he executed the project: from rough demos to lush orchestration.

ON CREATING AN EPIC:

When I was younger, I was smart enough to know the things that I didn’t know. What has been beneficial to me is that the framework of this story follows this one reactionary character who is completely ignorant from the beginning, right through all of the things that he experiences in his life. So for this project, I had to leave myself open to new experiences I would go through and draw from— which are now so much more than I could have drawn from at age 23.

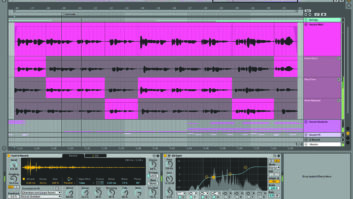

ON DEMOING THE PROJECT:

While I was writing it, I had about half of the record already demoed pretty much to a T. Then we got together and came up with some other ideas, played them through and demoed them as a band. Every single note was written out, but since we are all such gear-heads and tone junkies, once we were recording, we wanted it to be much more about discovering proper texture, tone and dynamics. When you are navigating your way through your library of pedals, amps, snare drums and kick drums, there is always something new to unlock, allowing you to play something different than you would have done before.

ON THE BASS OF “REBIRTH”:

Once we finished putting down the orchestral parts, I still felt like the track was missing something, so I added a bass. It is the only track I played bass on. I love the dueling bass approach of those old Beach Boys songs where there is an octave line shared between those two muted instruments and I wanted to have something like that: a percussive line on bass and guitar plunking its way through. For me, that was the cherry on top. There was already so much going on, but this helped add the low, percussive urgency on the opening part of the track.

ON THE BIG PICTURE:

Once we recorded everybody else’s stuff, after we were done with the two other guitar players’ guitars, I was alone for the rest of the process. There were many moments where I didn’t have other people to bounce ideas off of, so I had to throw my ego away and ask myself “Is this right for this?” There were plenty of songs that I had tracked entirely, where the vocals were done, comped and ready to go. But then I would listen and say, “this isn’t right” and go back to the drawing board. This kind of thing happened all the time. But the big picture was always there, and the big picture was the thing that I had to keep on referencing in my heart while I was working. When I would find myself obsessing about the smallest details, I had to remember the big picture and remember how important that perspective actually was.

ON OVERCOMING CHALLENGES:

Within every step of the production process, there was a much higher standard in the quality I wanted to achieve across the board. That meant a more meticulous approach to things like mic position, using the correct amount of compression and preparing the tracks properly before I handed them over to Mike Watts—who is a very good friend and who has mixed a lot of the stuff we’ve done. I didn’t want a single pop or click, or any wavering in microphone etiquette where I didn’t adjust something properly. Pulling off the orchestration parts was also extremely challenging, because I had to look at everything—drums, bass, guitar, pianos and vocals—and then consider the orchestra as one large ensemble in relation to this. I’d never done anything close to this on another Dear Hunter record, so this was a very challenging and required a lot of learning on my part.

ON DRAWING ON INFLUENCES:

This may sound cliché, but the thing that really made sense of everything for me was Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. It just unlocked something for me. After that, I fell in love with the technical side of preparing staff music, and everything became cyclical. I got more and more enjoyment out of relaying my ideas through this preexisting language of staff music and sheet music, and then handing this over to musicians who knew how to properly emote it. After that, I became more and more interested in what each of the instruments could do, and fell in love with certain tonalities that I never thought I would: for instance, the bassoon, the oboe and the woodwinds section.

ON STAYING BUSY:

I am so grateful for the opportunity to be in a studio making music and I love that privilege of being able to devote myself entirely to the process. I never take it for granted and I have never been interested in dead time or taking a break, because none of this is a chore. In fact, taking a break from it is not very fulfilling. I think I have an affinity for projects that are really ambitious, especially those that require a lot of care and immersion into detail. When I get the opportunity to sit down and really write, it is like a flood of ideas every time.