Bristol, UK (January 29, 2021)—In September 2020, U.K. reissue label Cherry Red acquired the “Tea Chest Tapes,” a fabled trove of nearly 1,900 quarter-inch tapes recorded by legendary London-based producer and engineer Joe Meek, featuring some of the biggest names in classic rock. Eyeing an eventual release, Cherry Red is now digitizing the tapes, a herculean task that has fortuitously fallen into the lap of the label’s longtime mastering engineer, Alan Wilson, a Meek aficionado.

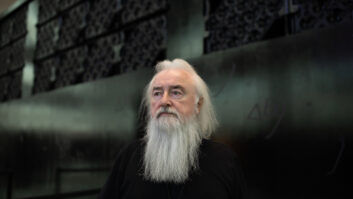

“I’m a lifelong Joe Meek fanatic, an analog tape specialist, a studio engineer and I’ve recorded and produced albums for as many of the Joe Meek artists as is possible,” says Wilson, including Mike Berry, Clem Cattini, Ray Fenwick, Chas Hodges and John Leyton. “I’ve also personally recorded three Joe Meek tribute albums over the years.” Wilson, whose psychobilly band The Sharks signed to Cherry Red in 1992, has owned and operated Western Star Studio in Bristol since 1999 and his own record label since 2003.

Meek is renowned as the first-ever independent record producer. His professional career, which lasted just 12 years, ending with his suicide on Feb. 3, 1967, was as prolific as it was successful. “Telstar,” by The Tornados, which he wrote and produced in 1962, was the first British rock record to top the U.S. singles charts, selling more than five million copies.

Meek was innovative, too, pioneering studio techniques such as close miking, aggressive compression and flanging. A gifted electronics designer, he made his own “black boxes,” including what is thought to be the first spring reverb. His designs have lived on, initially manufactured by his former studio assistant Ted Fletcher; today, Joemeek brand gear is now available from Alan Hyatt’s PMI Audio Group.

After the producer’s death in 1967, Cliff Cooper, bass player with Meek band The Millionaires, aspiring studio engineer and founder of then-fledgling Orange Amps, went to the estate sale in hopes of purchasing audio equipment. While he got there too late to buy gear, Cooper was offered 67 wooden tea chests full of tapes and figured he could listen to them to learn the production secrets held within; the cache changed hands for £300.

Little did he know that in time, the tapes would prove to be a musical bonanza, as a who’s who of future rock and pop royalty had passed through Meek’s studio flat at 304 Holloway Road in North London. David Bowie’s first recording, with The Konrads, was made there with Meek. Ritchie Blackmore was the producer’s go-to session guitarist for three years. Steve Howe, future Yes guitarist, brought his first band, The Syndicats, to the studio. Ray Davies of The Kinks wrote songs for The Honeycombs, for whom Meek produced several hits, including “Have I the Right.” The tape collection is said to also include material by Marc Bolan (age 15), Steve Marriott (age 16), Gene Vincent, Billy Fury, Georgie Fame, Alvin Lee, Jonathan King and three songs by an early line-up of the band that became Status Quo. All of it sat locked away in a temperature- and humidity-controlled vault, rarely played for more than 50 years.

Adding to the mystery surrounding the Tea Chest Tapes, the writing scrawled on the tape boxes didn’t necessarily reflect the contents; as a result, many years ago, Cooper had a Meek authority identify and catalog everything. Nonetheless, as Wilson discovered when he began to digitize the reels, there are still tracks to be documented. Tapes may be full-width mono or stereo, says Wilson, who is transferring them at a rate of 100 reels per month, “but you don’t know until you play them.”

As it turns out, the trove of tapes had some additional hidden treasure in it—lost music hidden within entirely different songs, a surprising situation caused by Meek’s tendency to reuse work tapes without blanking them first.

Saving the Bob Dylan Archive from Adhesion Syndrome

When Meek took old mono work tapes and reused them to record in stereo, the space between the left and right channels was never recorded over. As a result, when Wilson ran the first few tapes across a mono head, he says, “I could hear something else going on. I put them on an Otari MTR-12 4-track machine and just listened to the center two tracks. I was astonished to hear a completely different track than was on the left and right stereo, ‘beneath’ the tracks. It’s not much wider than a cassette tape track, but at 15 i.p.s., that’s a good piece of tape. The guy who cataloged everything 30 years ago wouldn’t have heard that on a stereo machine.” As a result, there’s potentially a lot of extra material if many other tapes have those underlying tracks, Wilson says.

As it stands, the tapes largely comprise masters of releases, alternate takes or track builds. “We’re finding a reel of tape that, say, is the backing track of someone like The Outlaws [Meek’s house band], but no vocal. We’ll find another tape and there’s vocals. And another, with added backing vocals. He was building things, bouncing from one machine to another to another.”

By and large, the tapes are in very good condition, he says. “We’re taking everything off with great care, using Otari machines, cleaning and baking where necessary.” As for the content, says Wilson, “The quality is quite stunning, even flat transfers, before we restore and master. It makes me realize how good Joe Meek was.”

For now, Cherry Red say it has no plans to release anything until every tape is digitized, a process that will take many more months. For a lifelong fan of Meek’s work, it will essentially be a labor of love.

“As you can imagine, this is the dream job,” says Wilson. “I’m very lucky to be working on this.”

Link: Western Star Recording Company • www.western-star.co.uk

Cherry Red • www.cherryred.co.uk